Hyperglycemia and diabetes are common in hospitalized patients. Managing that amid the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the more recent staff shortages, has been extremely difficult at the VA and elsewhere. Increased use of continuous glucose monitoring has helped the situation.

BALTIMORE — Diabetes significantly increases the risk of severe complications associated with COVID-19, making particularly important the careful monitoring of hospitalized patients with the condition.

At the same time, shortages of personal protective equipment early in the pandemic and a dearth of nurses and other health care workers in more recent waves have made traditional in-person finger sticks and paper-based systems for guiding insulin drips untenable in many situations.

Increasingly, too, patients with diabetes have arrived at the hospital with their own continuous glucose monitors in place. Globally, the continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system market is anticipated to more than quadruple from $4.31 billion at the start of the pandemic in 2020 to $17.8 billion by 2028, according to Emergen Research.

CGM growth continues to be driven by the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes, rising obesity rates and an aging population, along with strong evidence supporing the use of CGM to manage diabetes in the ambulatory setting. In 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration relaxed rules governing the use of CGMs, permitting deployment of Abbott and Dexcom CGMs in the inpatient setting during the pandemic. In March 2022, the FDA granted the first CGM breakthrough device designation for use in hospitals.

A recent meta-analysis by researchers at the Baltimore VAMC and the University of Maryland School of Medicine provides strong support for continuing the use of CGMs in hospitals.1 As approximately one-third of hospital patients have diabetes or hyperglycemia, even outside of the pandemic, adoption of CGMs in the inpatient setting could have significant effects on hospital policy and use of staff.2

The team, led by Elias Spanakis, MD, of the Baltimore VAMC and the University of Maryland, evaluated the research on in-hospital use of CGMs using a wide range of metrics and found “the use of inpatient CGM confers numerous benefits with minimal risks.”

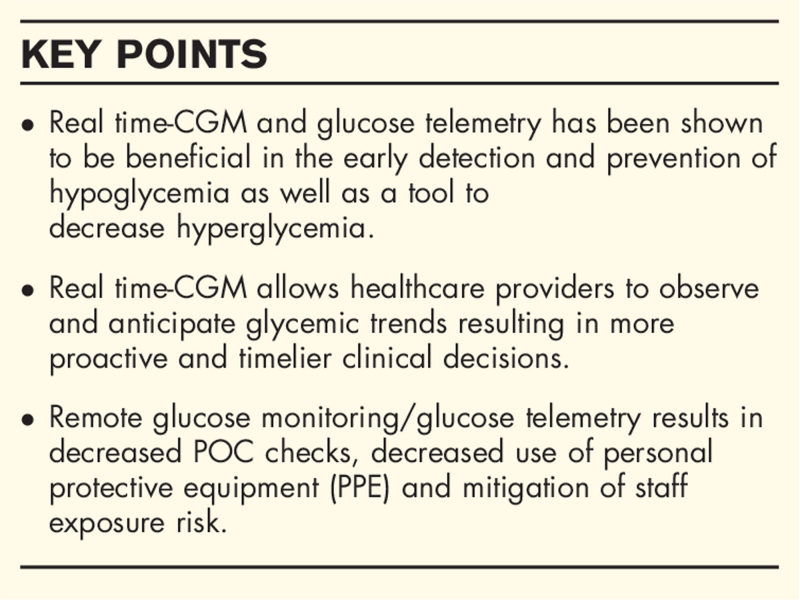

The devices reduced the incidence of hypoglycemia and improved management of hyperglycemia. In one study, patients using CGM with a glucose telemetry system (GTS) that transmitted data from the patient’s sensor to an iPhone and then to an iPad at the nursing station had fewer hypoglycemic events calculated as blood glucose below 70 mg/dL (0.67 [95% confidence interval, CI 0.34–1.30] vs. 1.69 [1.11–2.58], P = 0.024) and fewer clinically significant hypoglycemic events or blood glucose below 54 mg/dL (0.08 [0.03–0.26] vs. 0.75 [0.51–1.09], P = 0.003) compared to patients whose blood glucose was measured at point of care.

Less Hyperglycemia

Another study determined that real time-CGM also reduced the percentage of time spent in hyperglycemia compared to usual care, 27% vs. 33%. A third found that use of CGM significantly increased the time in range for patients with type 2 diabetes, 75.7% to 82.2%, and for those hospitalized for acute complications, 58.3% to 66.4%, over the period of hospitalization.

Multiple assessments of CGM systems during the pandemic determined that the technology provided accurate data and could be used for clinical decision-making and insulin titration, though nurses reported dissatisfaction with the length of time spent in a protocol designed to verify accuracy that required simultaneous use of CGM and usual care. Nearly two-thirds of nurses found the system helpful for managing clinical care, with studies indicating a reduction in point of care assessment of 50% to 63% and concomitant reduction in use of personal protective equipment.

The Baltimore team compared the transition to CGM to the move from serum blood glucose to point of care testing with glucometers. Just as glucometers have become the standard of care in recent decades, “we believe that CGM devices will eventually be utilized in the hospital as standard of care as they provide a more robust and enriched data set of glycemic values than glucometers, helping clinicians and nurses to safely manage patients with diabetes without increasing workload,” they said. “In conclusion, although CGM devices are currently seen as novel systems, it is only a matter of time when CGM systems will be approved for use in the inpatient setting.”

Another VA study looked at the use of an electronic glucose monitoring system (eGMS) compared to paper-based protocols for management of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome (HHS) in a retrospective study of veterans treated in the emergency department of intensive care unit at Veteran Health Indiana. Paper-based systems rely on patient weight to determine initial insulin drip rate and use a formula based on changes in blood glucose levels to adjust the drip. The electronic system adjusts doses by weight height, weight, age, sex, serum creatinine, steroid dosing, renal function, diabetes type, response to insulin and estimated residual extracellular insulin.3

The research team, led by Madeline Brown, PharmD, found that patients in the electronic system group had fewer hypoglycemic events. The authors concluded that “eGMS use has the potential to minimize hypoglycemia and glycemic variability in a critically ill veteran population by individualizing insulin drip titration based on a variety of patient-specific factors and providing reminders for staff to obtain [blood glucose] checks in a timely manner.”

- Gothong C, Singh LG, Satyarengga M, Spanakis EK. Continuous glucose monitoring in the hospital: an update in the era of COVID-19. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2022 Feb 1;29(1):1-9. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000693. PMID: 34845159; PMCID: PMC8711300.

- Swanson C, Potter D, Kongable G, Cook C. Update on inpatient glycemic control in hospitals in the United States. Endocrine Practice. 2017;17:853–861.

- Brown M, Roberts J, Smith C, Eash D. Safety and Effectiveness of the Use of an Electronic Glucose Monitoring System Versus Weight-Based Dosing Nomogram for Treatment of Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Syndrome in a VA Hospital. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2022 Feb 7:19322968221074710. doi: 10.1177/19322968221074710. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35128975.