While alcohol use disorder is common among U.S. veterans, it often doesn’t stand alone. Instead, AUD is frequently found as a co-morbid condition with other psychiatric diagnoses or post-traumatic stress disorder. The combinations make the condition riskier and harder to treat.

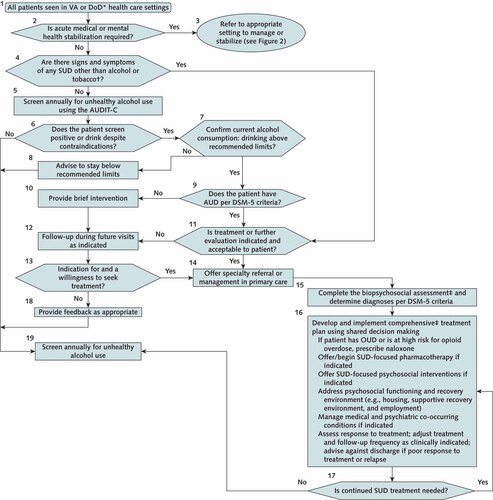

Click To Enlarge: AUD screening and treatment algorithm.

AUD = alcohol use disorder; AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption; DoD = U.S. Department of Defense; DSM-5 =Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; OUD = opioid use disorder; SUD = substance use disorder; VA = U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

* DoD active duty: Referral to specialty SUD care is required in any incident in which substance use is suspected to be a contributing factor. For refusal, contact Command to discuss administrative and clinical options.

† For patients with tobacco use disorder, refer to U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guideline on tobacco use.

‡ Specific to specialty care setting.

Source: VA/DoD Guideline Development Group

SAN DIEGO — Alcohol-use disorder is rampant among U.S. veterans and associated with substantial psychopathology, including heightened odds of suicidal behaviors, according to a new study.

“Results underscore the importance of comprehensive screening and preventive efforts for AUD, and interventions that concurrently target overlapping alcohol use and psychiatric difficulties,” wrote researchers from the VA San Diego Healthcare System.

The report in Drug & Alcohol Dependence pointed out, “Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a prevalent public health concern in the U.S. that disproportionately affects veterans relative to civilians. Given changes to the demographic composition of the veteran population and AUD diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5, updated knowledge regarding the epidemiology of DSM-5 AUD in a national sample of veterans is critical to informing the population-based burden of this disorder.”1

To reach their conclusions, researchers analyzed data from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study, which surveyed a nationally representative sample of 4,069 U.S. veterans. The study team assessed lifetime DSM-5 AUD (mild, moderate severe) and past-year DSM-5 AUD using evaluation of validated self-report measures and sociodemographic, military and psychiatric characteristics.

The study found that prevalence of lifetime and past-year DSM-5 AUD were 40.8% (95% confidence interval [CI]=39.2-42.3%) and 10.5% (95%CI=9.6-11.5%), respectively. In addition, the authors reported that lifetime prevalence of mild, moderate and severe AUD were 20.5%, 8.3%, and 12.0%, respectively.

“Veterans with lifetime AUD had elevated rates of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior, which generally increased as a function of AUD severity,” researchers noted. “Lifetime AUD was also associated with being younger, male, white, unmarried, retired and experiencing more adverse childhood experiences and traumas. For past-year AUD, being younger, male, white, having more adverse childhood experiences and experiencing lifetime PTSD were significant correlates.”

Other recent VA studies showed how certain comorbid conditions makes AUD even riskier for veterans.

Researchers from the Durham, NC, VA Health Care System noted, for example, that “posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcohol use disorder (AUD) are each common among United States (U.S.) military veterans and frequently co-occur (i.e., PTSD+AUD). Although comorbid PTSD+AUD is generally associated with worse outcomes relative to either diagnosis alone, some studies suggest the added burden of comorbid PTSD+AUD is greater relative to AUD-alone than to PTSD-alone.

Writing in the Journal of Affective Disorders, the authors further pointed out that nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is more common among veterans than assumed, although it is rarely measured as a veteran psychiatric health outcome.2

Their study sought to compare psychosocial functioning, suicide risk and NSSI among veterans screening positive for PTSD, AUD, comorbid PTSD+AUD and neither disorder. To do that, they analyzed data from a national sample of 1,046 U.S. veterans who had served during the Gulf War. A mailed survey was used to gather sociodemographic, functioning and clinical information.

AUD With PTSD

“Veterans with probable PTSD+AUD reported worse psychosocial functioning across multiple domains compared to veterans with probable AUD, but only worse functioning related to controlling violent behavior when compared to veterans with probable PTSD,” researchers wrote. “Veterans with probable PTSD+AUD reported greater suicidal ideation and NSSI than veterans with probable AUD, but fewer prior suicide attempts than veterans with probable PTSD.”

They went on to state that their findings “highlight the importance of delivering evidence-based treatment to this veteran population.” The authors cautioned, however, that their study was cross-sectional, relied on self-report, did not verify clinical diagnoses, and might not generalize to veterans of other military conflicts.

Another recent study discussed how veterans have high rates of both obesity and alcohol use disorder (AUD), which often co-occur. Researchers from the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven decried that, even though the conditions are prevalent and costly, information about clinical correlates between the two is lacking.

Their study recently published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research pointed out that the dearth of knowledge makes it difficult to find effective interventions.3

The study team analyzed data from a nationally representative sample of 4069 veterans–3,463 males and 479 females—completing an online survey. Researchers used the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test to identify veterans who screened positive for probable AUD (pAUD), while self-reported height and weight was used to calculate body mass index and identify veterans with obesity.

Multinomial logistic regression was used to examine differences between four groups:

- controls (no current AUD or obesity),

- pAUD only,

- obesity only, and

- pAUD + obesity.

Of the participants, 36.1% had obesity, 10.5% had pAUD and 3.7% had both.

Compared to veterans without AUD, veterans with pAUD were found to be less likely to have normal/lean weight (14.6% vs. 21.4%) and more likely to have overweight (49.6% vs. 41.7%).

Veterans with pAUD plus obesity also were nearly twice as likely than veterans with pAUD to report three or more adverse childhood experiences, the authors added.

“The results of this study help inform the clinical presentation and needs of veterans with co-occurring obesity and AUD,” researchers concluded. “They also underscore the importance of regularly monitoring weight among veterans with AUD and considering the role of childhood adversity as a risk factor for co-occurring AUD and obesity.”

- Panza KE, Kline AC, Na PJ, Potenza MN, Norman SB, Pietrzak RH. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder in U.S. military veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022 Feb 1;231:109240. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109240. Epub 2021 Dec 27. PMID: 34974271.

- Blakey SM, Griffin SC, Grove JL, Peter SC, Levi RD, Calhoun PS, Elbogen EB, Beckham JC, Pugh MJ, Kimbrel NA. Comparing psychosocial functioning, suicide risk, and nonsuicidal self-injury between veterans with probable posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder. J Affect Disord. 2022 Apr 7;308:10-18. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.006. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35398395.

- Carr MM, Serowik KL, Na PJ, Potenza MN, Martino S, Masheb RM, Pietrzak RH. Co-occurring alcohol use disorder and obesity in U.S. military veterans: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical features. J Psychiatr Res. 2022 Mar 24;150:64-70. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.03.039. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35358833.

- The Management of Substance Use Disorders: Synopsis of the 2021 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med.2022;175:720-731. [Epub 22 March 2022]. doi:10.7326/M21-4011