Differentiating the Causes of Seizures, Dementia Can Be Challenging

During the outcome period, 58 608 veterans died (20.1%); veterans with LOSU were more likely to die than those without LOSU (601 of 2166 [27.7%] vs 58 007 of 290 096 [20.0%]; P < .001). Incident dementia was diagnosed in 14 076 veterans, of whom 181 (1.3%) had prior LOSU. The mean (SD) follow-up time from LOSU diagnosis until an outcome was 6.1 (2.9) years.

Temporal lobe epilepsy patients have a heightened risk of cognitive impairment as they age. That creates special challenges for the VA, which treats about 90,000 veterans diagnosed with epilepsy and many more who have unidentified seizure disorders, which also are linked to cognitive problems later in life.

SAN DIEGO — Over the past decades, a lot of VA research has focused on younger, post-9/11 veterans and the difficulty in differentiating psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNEs) from epilepsy.

A similar conundrum exists with older veterans, however. While cognitive impairment can be a typical comorbidity in epilepsy, appearing in a significant number of older adults with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), the development later in life of seizures—which might or might not be symptoms of epilepsy—also are strong indicators of cognitive impairment. Determining the etiology of the seizures and the cognitive issues can determine appropriate treatment.

About 90,000 VA healthcare system patients have a diagnosis of epilepsy, and many more have unidentified seizure disorders. The outsize risks of cognitive impairment in those veterans has critical implications for the VA.

A recent study led by the University of California San Diego and including participation from the VA San Diego Healthcare System sought to characterize the nature and prevalence of cognitive disorders in older adults with TLE. Reporting in the journal Epilepsia, researchers compared cognitive profiles in those patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI).1

Included in the study from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative were 71 older patients with TLE; of those, 77 had aMCI, and 69 were normal aging controls (NACs), all 55‐80 years of age. Participants completed neuropsychological measures of memory, language, executive function and processing speed.

Researchers applied an actuarial neuropsychological method designed to diagnose MCI to individual patients to identify older adults with TLE who met diagnostic criteria for MCI (TLE‐MCI). They also performed a linear classifier to evaluate how well the diagnostic criteria differentiated patients with TLE‐MCI from aMCI. Also evaluated was the contribution of epilepsy‐related and vascular risk factors to cognitive impairment.

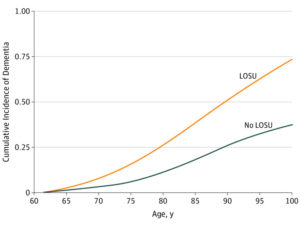

Cumulative Incidence of Dementia Adjusted for Demographic Characteristics and Comorbid Conditions in Patients With and Without Late-Onset Unprovoked Seizures of Unknown Etiology (LOSU)

Ultimately, 43 patients (60%) met criteria for TLE‐MCI (i.e., demonstrating substantial deficits in both memory and language). Analyzed according to age at seizure onset, 63% of patients with an early onset, defined as younger than 50, vs. 56% of those with late onset, defined as 50 or older, met criteria for TLE‐MCI.

The authors advised that a classification model between TLE‐MCI and aMCI correctly classified 81.% (90.6% specificity, 61.3% sensitivity) of the cohort based on neuropsychological scores.

“Whereas TLE‐MCI showed greater deficits in language relative to aMCI, patients with aMCI showed greater rapid forgetting on memory measures,” they wrote. “Both epilepsy‐related risk factors and the presence of leukoaraiosis on MRI contributed to impairment profiles in TLE‐MCI.”

Researchers said their findings were significant, pointing out, “Although the underlying etiologies are unknown in many patients, the TLE‐MCI phenotype may be secondary to an accumulation of epilepsy and vascular risk factors, signal the onset of a neurodegenerative disease, or represent a combination of factors.”

While those studies looked specifically at patients diagnosed with temporal lobe epilepsy, other veteran research cast a wider net and focused on how the incidence of unprovoked seizures and epilepsy increases considerably in late life, with approximately one-third of seizures being of unknown etiology.

“While individuals with dementia have a high risk of developing unprovoked seizures, it is unknown whether older adults with late-onset unprovoked seizures of unknown etiology (LOSU) are at risk of developing dementia,” wrote the authors from the San Francisco VA Health Care System and the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

That study team sought to determine whether incident LOSU is associated with a higher risk of dementia among older veterans; the retrospective multicenter cohort study used date from VHA medical centers from October 2001 to September 2015. Included were all veteran inpatient and outpatient encounters.

From the random sample of 941,524 veterans 55 years and older that was generated, researchers focused on 292,262 veterans previously diagnosed using ICD-9-CM codes with dementia, unprovoked seizures, epilepsy, and conditions that could lead to seizures—brain tumors, trauma, infections, stroke and neurotoxin exposure. Participants, who were required to have follow-up data, were 96.7% male and had a mean age of 73. Analysis occurred from October 2018 to July 2019.

The authors explained, “Late-onset unprovoked seizures of unknown etiology were defined as a new diagnosis of epilepsy or unprovoked seizures without a diagnosis of a secondary cause for seizures. Incident LOSU was assessed during a 5-year baseline period.”

During the baseline period, 2,166 veterans developed LOSU and were followed for a mean of 6.1 years. The researchers reported that, after multivariable adjustment, veterans with LOSU had greater risk of dementia compared with veterans without seizures (hazard ratio, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.62-2.20), according to the article in JAMA Neurology.2

Double Dementia Risk

“These findings suggest LOSU in older veterans is associated with a 2-fold risk of developing dementia,” the authors concluded. “While seizures are commonly thought to occur in late stages of dementia, these findings suggest unexplained seizures in older adults may be a first sign of neurodegenerative disease.”

A study using data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort study, which started in 1987 to 1989 with 15,792 participants from four U.S. communities, also found the risk of incident dementia is significantly elevated in patients with diagnosed late-onset epilepsy.

“Further work is needed to explore causes for the increased risk of dementia in this growing population,” wrote the authors from the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health in Baltimore.

They reported recently in Neurology that, of 9,033 ARIC participants with sufficient Medicare coverage data (4,980 [55.1%] female, 1993 [22.1%] Black), 671 met the definition of LOE. Dementia occurred in 279 (41.6%) of participants with and 1,408 (16.8%) without LOE. In fact, the researchers determined that, after a diagnosis of LOE, the adjusted hazard ratio for developing subsequent dementia was 3.05 (95% confidence interval 2.65-3.51), with the median time to dementia ascertainment after the onset of LOE at 3.66 years (quartile 1-3, 1.28-8.28 years).

Distinguishing between the epilepsy-related condition and mild cognitive impairment remains difficult, however, according to a recent study in Brain.3

“Epilepsy incidence and prevalence peaks in older adults yet systematic studies of brain ageing and cognition in older adults with epilepsy remain limited,” wrote University of California San Diego-led authors.

The study team characterized patterns of cortical atrophy and cognitive impairment in 73 older adults with temporal lobe epilepsy and compared those patterns to those observed in 70 healthy controls and 79 patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment, the prodromal stage of Alzheimer’s disease.

“Older adults with temporal lobe epilepsy demonstrated a similar pattern and magnitude of medial temporal lobe atrophy to amnestic mild cognitive impairment,” the researchers found. “Region of interest analyses revealed pronounced medial temporal lobe thinning in both patient groups in bilateral entorhinal, temporal pole and fusiform regions (all P < 0.05).”

On the other hand, they explained, “Patients with temporal lobe epilepsy demonstrated thinner left entorhinal cortex compared to amnestic mild cognitive impairment (P = 0.02). Patients with late-onset temporal lobe epilepsy had a more consistent pattern of cortical thinning than patients with early-onset epilepsy, demonstrating decreased cortical thickness extending into the bilateral fusiform (both P < 0.01).”4

Still, the authors noted that both temporal lobe epilepsy and amnestic mild cognitive impairment groups had significant memory and language impairment as compared to healthy control subjects. One difference, they pointed out, was that patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment had poorer delayed memory performances vs. both early and late-onset temporal lobe epilepsy.

“Medial temporal lobe atrophy and cognitive impairment overlap between older adults with temporal lobe epilepsy and amnestic mild cognitive impairment highlights the risks of growing old with epilepsy,” the authors concluded. “Concerns regarding accelerated ageing and Alzheimer’s disease co-morbidity in older adults with temporal lobe epilepsy suggests an urgent need for translational research aimed at identifying common mechanisms and/or targeting symptoms shared across a broad neurological disease spectrum.”

-

Reyes A, Kaestner E, Edmonds EC, Christina Macari A, Wang ZI, Drane DL, Punia V, Busch RM, Hermann BP, McDonald CR; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Diagnosing cognitive disorders in older adults with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2021 Feb;62(2):460-471. doi: 10.1111/epi.16780. Epub 2020 Dec 1. PMID: 33258159.

-

Keret O, Hoang TD, Xia F, Rosen HJ, Yaffe K. Association of Late-Onset Unprovoked Seizures of Unknown Etiology With the Risk of Developing Dementia in Older Veterans. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Jun 1;77(6):710-715. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.0187. PMID: 32150220; PMCID: PMC7063560.

-

Johnson EL, Krauss GL, Kucharska-Newton A, Albert MS, Brandt J, Walker KA, Yasar S, Knopman DS, Vossel KA, Gottesman RF. Dementia in late-onset epilepsy: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Neurology. 2020 Dec 15;95(24):e3248-e3256. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011080. Epub 2020 Oct 23. PMID: 33097597; PMCID: PMC7836657.

-

Kaestner E, Reyes A, Chen A, Rao J, Macari AC, Choi JY, Qiu D, Hewitt K, Wang ZI, Drane DL, Hermann B, Busch RM, Punia V, McDonald CR; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Atrophy and cognitive profiles in older adults with temporal lobe epilepsy are similar to mild cognitive impairment. Brain. 2021 Feb 12;144(1):236-250. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa397. PMID: 33279986; PMCID: PMC7880670.