Outside partnerships have helped the VA improve access to and the use of both tumor testing for somatic mutations and germline testing for hereditary mutations in prostate cancer. Improved responses to targeted medications plus better adherence to guidelines for treatment intensification appeared to be having a positive effect for metastatic disease.

DURHAM, NC — Veterans face twice the risk of prostate cancer compared to those who have never served, with approximately 15,000 veterans diagnosed with the disease annually. Breakthroughs in treatment have allowed those patients to live longer than ever and swelled the number of veterans with prostate cancer receiving care through the VHA to nearly 500,000.

While treatment for localized prostate cancer (PC) can be curative, about half will progress to metastatic disease following treatment for localized disease and a further 8% of patients will have distant metastases at diagnosis.

Several studies involving VA researchers recently examined treatment selection in metastatic PC, the first looked at adherence to and the impact of guidelines for treatment intensification in veterans with metastatic castration-sensitive PC (mCSPC), while the others analyzed molecular testing and treatment in veterans with metastatic castration-resistant PC (mCRPC).

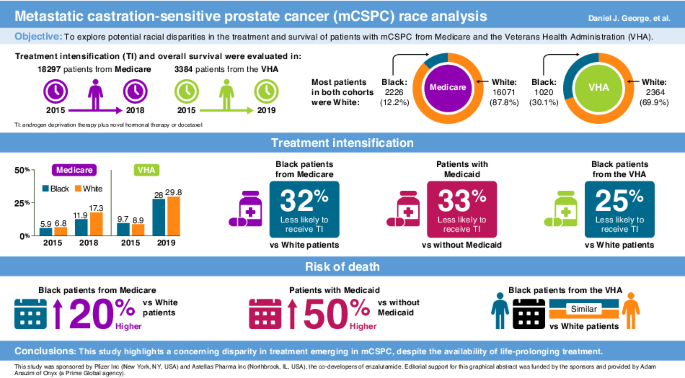

Researchers at the Durham VAMC and Duke University School of Medicine, both in Durham, NC, drew on data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Fee-for-Service beneficiaries from Jan. 1, 2015, to Dec. 31, 2018, and the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse from Jan. 1, 2015, to June 22, 2019, to compare treatment selection in mCSPC by race.1

They found that, while Black veterans were less likely to receive guideline-recommended treatment intensification than white veterans, there was no difference in overall survival. The same was true for dual Medicare/Medicaid beneficiaries. Among Medicare-only beneficiaries, however, treatment intensification and overall survival were notably lower for Black vs. white patients.

All patients in the study were followed from date of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) treatment initiation until death, end of enrollment or end of data availability, whichever came first.

The Medicare group included 2,226 Black patients (12.2%) and 16,071 white patients (87.8%). Of those, 40.3% of Black and 9% of white patients were dual enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid. In the VHA group, 30.1% of the patients (1020) were Black and 69.9% (2364) were white. Black patients were younger on average than white patients in both groups, with mean age of 73.9 vs. 76.9 years and 70.1 vs. 74.4 years, in the Medicare and VHA groups, respectively.

During the study period, consensus guidelines recommended treatment intensification for all patients with mCSPC based on evidence that adding docetaxel, novel hormonal therapy (NHT) with abiraterone, apalutamide or enzalutamide or both docetaxel and NHT to ADT significantly improved survival. Yet, first-line treatment intensification (TI) improved only slowly across the board, though veterans were almost twice as likely to receive guideline-directed care with TI on average compared to Medicare beneficiaries, 19.9% vs. 10.3%, respectively.

Among Medicare patients, the proportion who had treatment intensification (TI) rose from 5.9% to 11.9% in Black patients and from 6.8% to 17.3% for white patients. Among veterans, the proportion receiving TI increased from 9.7% in 2015 to 28.0% in 2019 for Black patients and from 8.9% to 29.8% for white patients.

After adjustment for patient characteristics, Black patients with Medicare alone were 30% less likely to receive TI than their white counterparts. Among dual-enrolled beneficiaries, there was no difference by race, but all those with Medicaid were 33% less likely than those with Medicare only to receive TI.

On an adjusted basis, Black veterans were 25% less likely to receive TI than white veterans, but there was no significant difference in median overall survival on an adjusted or unadjusted basis, 43.6 (38.1-50.3) months for Black veterans and 42.2 (39.7-45.5) months for white veterans.

Given that prostate cancer tends to be more aggressive in Black patients, the lower levels of TI raised some questions among the researchers. In connection with the disparity among veterans, lead author Daniel J. George, MD, told U.S. Medicine, “I was surprised that with equal insurance, that there was a difference in terms of intensification rates. One factor might be other nonclinical differences that may associate with race, including social determinates of health.”

As to the lack of difference in overall survival rates among veterans despite a difference in treatment intensification rates, George noted, “We focused only on patients with metastatic prostate cancer, so the differences in rates of aggressiveness by race may be negated when we eliminated patients with non-metastatic prostate cancer (more commonly in white patients). Next, focusing on the metastatic setting, the early deaths may be driven by the most aggressive cancers in both races where the disease is not solely dependent on hormonal signals. I suspect that over time we will see a difference in survival, but it may take longer follow up and more patients.”

Molecular Testing

Treatment intensification can slow or prevent metastatic prostate cancer from becoming castration resistant or failing to respond to ADT, but still, many patients will develop this more challenging form of the disease. In recent years, treatment options for mCRPC have multiplied, offering hope for longer survival.

Many of the new treatments for mCRPC, however, are targeted therapies that require tumor testing for appropriate selection. Consequently, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend genetic testing for all patients with metastatic prostate cancer, which can identify those with actionable homologous recombination repair (HRR) pathway mutations and other variants with therapeutic targets.

In partnership with the Prostate Cancer Foundation since 2016, the VA has striven to improve access to and use of both tumor testing for somatic mutations and germline testing for hereditary mutations that could affect response to targeted medications. A partnership with Foundation Medicine Inc. established in 2019 dramatically increased comprehensive genomic profiling.

Of 9,852 veterans with mCRPC diagnosed between 2016 and 2021, 20% received tumor testing, with nearly three-quarters of that testing occurring in 2020 and 2021. In 2016-2017, less than 2% of veterans received testing. Testing rates rose rapidly after 2019, reaching 33% in 2020 and 40% in 2021.2

Of those tested, 15% were positive for a pathogenic HRR mutation, such as BRCA2, for which poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors olaparib and rucaparib are approved treatments. Other therapies for common mutations include pembrolizumab for prostate cancer patients with microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair-deficient (dMMR) cancer.

As metastatic prostate cancer is a highly heterogeneous disease, increased testing to identify new therapeutic targets and better match treatments is needed.

A recent study found two new clusters of mutational signatures that bear further analysis. These included known clinically actionable mutations in SMO, ABL1, MET, ALK, FGFR2, and JAK3. “Additionally, we identified mutations in SMAD4/TGFβ (NCT02452008), ROS1, PTEN, EGFR, and BRAF, where therapies are currently being explored in the MATCH Trial (NCT02465060). We also identified mutations in GNAS that warrant further clinical exploration if confirmed in another larger cohort,” the researchers noted.3

- George DJ, Agarwal N, Ramaswamy K, Klaassen Z, et. Al. Emerging racial disparities among Medicare beneficiaries and Veterans with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2024 Apr 2. doi: 10.1038/s41391-024-00815-1.

- Hung A, Candelieri D, Li Y, Alba P, et. Al. Tumor testing and treatment patterns in veterans with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Semin Oncol. 2023 Feb-Apr;50(1-2):11-24.

- Hernandez KM, Venkat A, Elbers DC, Bihn JR, et. Al. Prostate cancer patient stratification by molecular signatures in the Veterans Precision Oncology Data Commons. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2024 Jan 10;9(4):a006298.