The risk of adverse long-term outcomes, including cardiovascular disease, dementia, epilepsy and mental health issues, is well known for servicemembers and veterans suffering from traumatic brain injury (TBI). A new study of post-9/11 veterans, however, has raised the specter that TBI also might make patients more vulnerable to brain cancer.

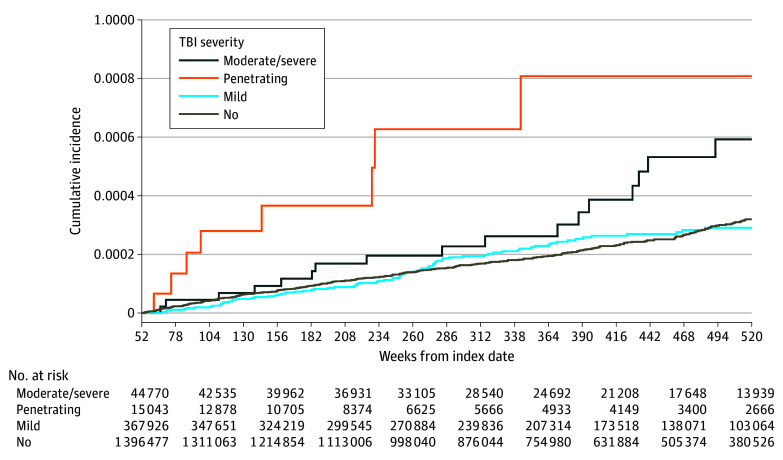

Click to Enlarge: Cumulative Incidence Functions for the Outcome of Malignant Brain Cancer Stratified by Traumatic Brain Injury Severity.

TBI indicates traumatic brain injury. Source: JAMA Network Open

BETHESDA, MD — Traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been linked to poor long-term outcomes in the veteran population, including cardiovascular disease, dementia, epilepsy and mental health issues. A new study of post-9/11 veterans provides evidence of yet another concerning effect of TBI—an increased, although still low, risk of brain cancer.

Led by Ian J. Stewart, MD, of the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, the study is the first to examine the potential association between TBI and brain cancer in a veteran cohort.

Stewart, whose research focuses largely on the effects of combat injury and trauma, became interested in a possible connection between TBI and subsequent brain cancer when a colleague, Michael Dore, MD, told him that two of his patients with multiple TBIs had been diagnosed with glioblastoma. While glioblastoma is the most common form of brain cancer, it is still quite rare, affecting 3.21 per 100,000 population.

“Given how rare that diagnosis is, he thought it was quite a coincidence that they both happened to get that brain cancer,” Stewart told U.S. Medicine. “He wanted to see if we had any data and could look at this in a systematic fashion.”

As it so happened, they did—in the form of the Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium–Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (LIMBIC-CENC) database, Stewart said. The LIMBIC-CENC is a comprehensive research network for DoD and VA with the goal of looking at TBI and the outcomes after TBI, so examining a connection between TBI and brain cancer fit nicely into that goal, he said.

Using data from 1,919,740 veterans with a median follow-up of 7.2 years, the researchers classified brain cancer on the basis of administrative codes and death codes and then conducted a Fine and Gray analysis, “which basically gives us the risk of developing a brain cancer while adjusting for the competing endpoint of death,” Stewart said. TBI severity was categorized as mild, moderate/severe and penetrating.1

The cohort included 449,880 individuals with TBI—385,848 mild; 46,859 moderate/severe; and 17,173 penetrating. Brain cancer occurred in 318 individuals without TBI (0.02%), 80 with mild TBI (0.02%), 17 with moderate/severe TBI (0.04%), and 10 or fewer with penetrating TBI (≤0.06%).

“[After adjustment] we found that mild TBI was not associated with subsequent brain cancer, but both moderate and severe TBI and also penetrating TBI were associated with subsequent brain cancer,” Stewart said.

While the new study was the first to establish a link between TBI and brain cancer in post-9/11 veterans, Stewart said a link between TBI and subsequent brain cancer has been recognized as biologically plausible for some time. He cited a 1978 study of a rat model for neural tumors found that animals exposed to a cerebral stab wound were more likely to develop gliomas compared with uninjured control animals.2

More recently, researchers who performed single-cell RNA sequencing on glioblastoma stem cells from 26 individuals found that these cells “mapped to states reminiscent of neural development and the inflammatory wound response.” Based on these results, that study’s authors postulated that glioblastoma may arise as a response to injury, such as TBI, in patients with a mutated genomic background.3

‘Scientifically Plausible’

“The idea is that TBI is going to cause inflammation that is going to turn on repair mechanisms, so potentially in someone at high risk, TBI can be the thing that tips [them] over into getting the diagnosis,” said Stewart. “That is very speculative—just a theory, by no means proven, but it is scientifically plausible.”

Although the risk of brain cancer was almost doubled with moderate/severe TBI in the new study, Stewart offered the assurance that the risk is still small. “The issue is that brain cancer is a very rare diagnosis. If you take a very small number and double it, you still have a very small number,” he said. “Even for a patient with more severe TBIs, brain cancer is still not a likely outcome.”

Right now, the study’s message is one of awareness, Stewart said. “Unfortunately, we don’t have any recommendations with regard to screening or something like that. It wouldn’t be effective to screen all of these people over a period of time, given how rare this diagnosis is. But what I think this underscores is [that] we really need to have a better understanding of brain cancer and TBI and, frankly, other diagnoses after TBI that we have also looked at. If we can build better models and get better risk prediction, then potentially we can begin to talk about things like screening.”

The study is one of many—and there are more on the way, Stewart added—showing patients with TBI are at risk for a wide variety of chronic medical conditions. “I think the most important thing to take away from this is that the trajectory of these people’s lives has forever been changed,” he said. “They are at increased for a wide variety of things, and now brain cancer is another one of those things we can add to the list.”

- Stewart, I. J., Howard, J. T., Poltavskiy, E., Dore, M., et al. (2024). Traumatic Brain Injury and Subsequent Risk of Brain Cancer in US Veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars. JAMA network open, 7(2), e2354588. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.54588

- Morantz, R. A., & Shain, W. (1978). Trauma and brain tumors: an experimental study. Neurosurgery, 3(2), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1227/00006123-197809000-00009

- Richards, L. M., Whitley, O. K. N., MacLeod, G., Cavalli, F. M. G., et al. (2021). Gradient of Developmental and Injury Response transcriptional states defines functional vulnerabilities underpinning glioblastoma heterogeneity. Nature cancer, 2(2), 157–173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-020-00154-9