Activated phosphoinositide 3-kinase delta (PI3Kδ) syndrome (APDS), is an extremely rare congenital immunodeficiency syndrome. Currently, the number of patients with the condition in the United States is thought to be fewer than 1,000, but that could change with increased genetic testing availability. For the first time, the FDA has approved a therapy which has been to the DoD formulary.

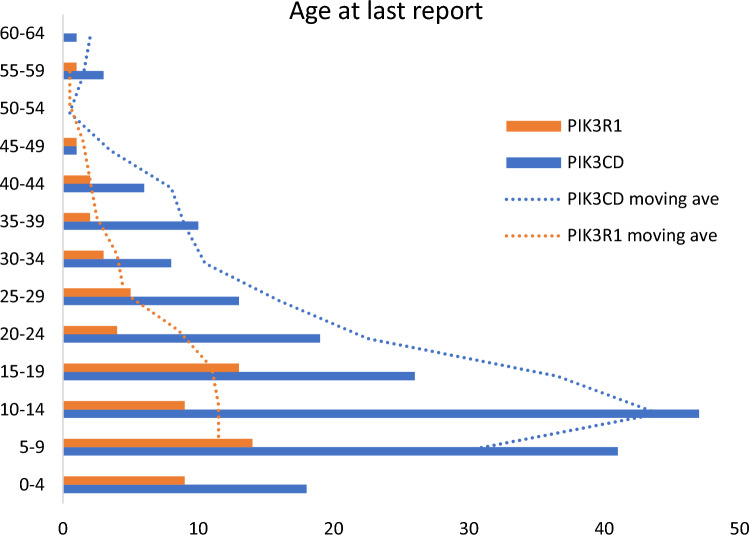

Click to Enlarge: Age at last report in a cohort of 256 individuals with APDS. The age at last report was plotted in 5-year age bins for individuals with a molecular diagnosis of pathogenic PIK3CD variant resulting in APDS1 (orange), and for those with a molecular diagnosis of pathogenic PIK3R1 variant (blue). The moving average of the age at last report was plotted for individuals with APDS1/PIK3CD in blue and for individuals with APDS2/PIK3R1 in orange Source: Springer

BETHESDA, MD — A phase III study led by a researcher at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has resulted in the first approval of a drug for activated phosphoinositide 3-kinase delta (PI3Kδ) syndrome (APDS), a rare congenital immunodeficiency syndrome.

With its approval, the DoD’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee has added the drug, leniolisib, to the uniform formulary for treatment of MHS beneficiaries aged 12 and older who weigh at least 45 kg and have diagnosed, symptomatic APDS.

Previously called p110 delta-activating mutation causing senescent T cells, lymphadenopathy and immunodeficiency (PASLI), APDS generally presents as recurrent infections starting in childhood. The disease is caused by mutations in either the genes PIK3CD (type 1) or PIK3R1 (type 2), which are typically inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, with children having a 50% chance of inheriting the variant. The gene also occasionally arises spontaneously. Both types result in hyperactive PI3Kδ signaling and similar immunologic complications.

The condition is extremely rare and is thought to affect about 1 to 2 people per million worldwide. In the United States, it is estimated that there are about 400 to 600 patients, although that number is expected to increase with the availability of genetic testing for APDS.

Researchers at the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) led by Carrie Lucas, PhD, now of the Yale School of Medicine, as well as V. Koneti Rao, MD, of the NIH NIAID, who led the phase III trial, and others discovered the link between the mutations and APDS in 2013.1

Symptoms of APDS include frequent sinopulmonary infections, lymphadenopathy, nodular lymphoid hyperplasia, fatigue and chronic or recurrent infections with cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein Barr virus (EBV), herpes virus or varicella zoster with severely deficient naïve and central memory T cells and excess senescent effector T cells. APDS is also associated with gastrointestinal issues, and bronchiectasis. Up to 25% of APDS patients develop lymphoma.

Treatment for APDS previously focused on symptom relief with prophylactic antibiotics and antivirals to control recurrent infections, anti-inflammatory drugs to treat cytopenia and other autoimmune diseases, immunoglobulin replacement to reduce respiratory infections and hematopoietic stem-cell transplant (HSCT) to treat lymphoma and life-threatening infections. Treatment with rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor, is used to decrease nonneoplastic lymphoproliferation.

APDS is associated with a shortened lifespan, with the largest study of survival and mortality for APDS showing conditional survival rate at age 20 of 87%, 74% at age 30, and 68% at ages 40 and 50. Lymphoma is the most-common cause of death, which had a mortality rate of 47.6%, followed by complications from HSCT, which had a 15.6% overall mortality rate.2

Restores the Balance

Leniolisib is a potent, selective oral inhibitor that targets PI3Kδ signaling and restores the balance between immature and functional B and T cells.

The phase III study enrolled 31 patients from the U.S., Europe and Russia between the ages of 12 and 75 years of age with symptomatic, diagnosed APDS and at least one measurable lymph node on computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. The study was, and placebo-controlled using a fixed-dose of 70 mg leniolisib or placebo at 12 hour intervals. Twenty-one participants were randomized to receive the study drug; 10 to receive a placebo.3

The 12-week subject-, investigator-, and sponsor-blinded study included efficacy and safety assessments on days 15, 29, 57 and 85 along with pharmacokinetic assessments on days 29, 57 and 85. The primary endpoints were reduction in size of lymph nodes and increase at day 85 in the percentage of naïve B cells out of all B cells ass assessed by flow cytometry. All patients had less than 48% naïve B cells at study initiation.

Secondary and exploratory endpoints included changes in bidimensional size and 3D volume of the spleen and liver, immunophenotyping of B- and T-cell subsets, and levels of serum immunoglobulins, cytokines, chemokines and inflammatory markers. The researchers also measured EBV and CMV loads.

“By day 85 of the study, patients taking Joenja [leniolisib] saw a reduction in lymph node size and a 37% improvement in naïve B cells counts compared to placebo, indicating a correction of the underlying immune defect,” the FDA said in its announcement of the drug’s approval. The difference in the adjusted mean change between leniolisib and placebo was 25%.

In addition, spleen volume declined substantially more with leniolisib than placebo (adjusted mean difference in 3-dimensional volume [cm3], −186; 95% CI, −297 to −76.2; P = 0.0020). Key immune cell subsets also improved.

A lower percentage of participants in the leniolisib group than in the placebo group reported study-related adverse events, 23% and 30%, respectively, with most grade 1 or 2. The most common side effects were headache, sinusitis and atopic dermatitis.

The FDA noted that leniolisib may cause fetal harm, adding that patients should be advised of the potential risk to a fetus and patients’ pregnancy status should be verified before starting treatment. In addition, patients with moderate to severe hepatic impairment should not use leniolisib, noted the FDA.

- Lucas CL, Kuehn HS, Zhao F, Niemela JE, et. Al. Dominant-activating germline mutations in the gene encoding the PI(3)K catalytic subunit p110δ result in T cell senescence and human immunodeficiency. Nat Immunol. 2014 Jan;15(1):88-97. doi: 10.1038/ni.2771.

- Hanson J, Bonnen PE. Systematic review of mortality and survival rates for APDS. Clin Exp Med. 2024 Jan 27;24(1):17. doi: 10.1007/s10238-023-01259-y.

- Rao VK, Webster S, Šedivá A, Plebani A, et. Al. A randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of the PI3Kδ inhibitor leniolisib for activated PI3Kδ syndrome. Blood. 2023 Mar 2;141(9):971-983. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022018546.